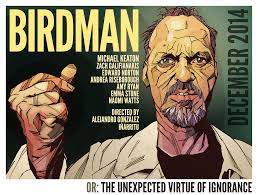

Having now watched the movie Birdman,

it sure has got me thinking about some, perhaps, not so obvious

connections.

There is a two sided consideration that

sticks out for me in this story. Something beyond the usual aspects

of an actor who, even though is suggest as being something more than

nominally human, is struggling with the relative values of what he

has, and has not achieved, throughout his career; juxtaposed, of

course, with a personal life that is a shambles. That is not only the

consideration of what makes for excellence in the craft of acting

itself, but what gives this endeavor value in the first place.

This idea takes prominence not only

because the main character (played by Michael Keaton) wants to be

taken seriously, after having gained financial success for portraying

a super hero, but also because of the tension that arises between him

and another actor brought in as a last minute replacement for someone

Keaton's character found lacking.

The new player (played by Edward

Norton), is a fairly established Broadway name with some serious

street cred. An actor who quickly demonstrates that he can act. The

problem, however, quickly becomes clear that this guy is a “Method”

actor at the essence of extreme. He makes becoming the person

portrayed the only real aspect of his otherwise pathetic life. And,

as the rest of the cast that Keaton's character has employed to make

this play happen, recoils at the Norton's characters behavior, both

on and off the stage, you start to wonder about what this says

concerning the craft of acting.

What has happened to such a time

honored, creative endeavor, over the centuries, to have brought it to

the point where the story, and the themes of that story, pale in

importance to the fidelity of how it is presented. And more to the

point, that it is, as much as anything else, a competition to see who

is best at being someone else. A competition that evolved the

competitors to the point of no longer seeing themselves as people

working a craft as professionals, but as just rewritable wetware

waiting for the next persona to assume completely.

The answer to that question is, it

seems to me, quite obvious. This is so because portrayal is a

commodity now pure and simple. Story may still have a place to one

degree or another, but the simple fact of the matter is that

fidelity, and the quick fix impact that multi sensory fidelity can

bring to the table of commodity, and the inherent competition that

surrounds all aspects of commodity, makes this absolutely mandatory.

A fact that the movie “The Congress” made only too depressingly

clear.

What resonates for me now, however, in

this context is how this example of commodity and competition

demonstrates another facet of what those two elements do the human

condition. Not only do we all now behave in everyday interaction as

actors on a state of a sort (secretly wishing we had real-time

monitors to keep track of how we were coming across—which I'm sure

that Google and their ilk will provide us with shortly), but we

consume ourselves with the competition of who is the most admired; a

thing quite apart from the relative notion of what is the best.

In this context views are the primary

thing that matters as far as admiration is concerned. Big view

numbers can may times automatically equate to admiration whether the

reaction to the content is good or bad on the whole. Being the best

in one fashion or another still carries weight of course, but total

numbers, and the all important demographic, are what most concern the

purveyors of commodity.

The problem, though, is that having a

“most admired,” as well as the “the best” in a more general

sense of demonstrable skill, plays so well into branding. Attaching

by association an implied aspect of one to the other. And because

this has become an all encompassing, immersive aspect of everyday

life, we hardly notice anymore how much of an effect it can have on

the choices we make. That being the case, those being so crowned,

however briefly, give us our main sense of what truly being valued

is; of what is the bottom line for being relevant. The rest of us,

toiling away in whatever small part of the machine that constitutes

production, commodity, and consumption, are left to try and convince

ourselves that, whatever goals those singular tasks allow us to

achieve, it has to be enough to continue treading along; working,

screwing, consuming, defecating, and just showing up so as to keep it

all going.

Is it any wonder that people have

resorted to doing the dumbest, or cruelest, or most destructive

things simply to be noticed? Is it any wonder that, even if you get

paid enormous sums for doing whatever, you can still feel completely

irrelevant? Not really appreciated because, in the sense that it now

has become understood as all that matters, you are not at all real.

That this sense can be, supposedly, satiated only by having a place

to stage really big view numbers.

And thus do we see the advantages of

becoming a brand that everyone recognizes. With that kind of labeling

you can be anywhere without having to act at all. You can assume the

validation of whatever audience you might find yourself in front of

because the persona has been established. You can relax. Just go

through the motions and the lines already scripted and bask in the

new real.

The bottom line for me is this: A day

will have to come when we recognize the relativity of being

marginally better at any given point in time, at what ever ability

you might care to consider. Testing ourselves against each other can

be a very useful, and healthy thing, certainly as it helps to

encourage aspiring to be better. Saying that, however, does not in

any way preclude the acceptance that there can always be too much of

any good thing. In this context it has always seemed to me that the

most courageous of us are exactly the “also rans.” For never let

us never forget that without them there can be no winner in the first

place; a fact that we lose sight of at our collective peril.

A society, or a culture for that

matter, doesn't live or die by its “winners.” It survives and

prospers by the quality of grit in its foundation. The kind of grain

of its granules in other words. We get a good grain in that sense

when we work the best balance of giving each individual a chance to

achieve not only personal goals, but locally recognized goals

important to the community. And it seems to me that the best way to

do that is to set things up so that absolutely clear that everyone is

needed to keep the community going. Once you have that as a basis to

work from you can then add on layers of additional recognition for

useful areas of ability competition (as in local, regional and

above). Recognition that has nothing to do with branding or the

market mentality that goes with it. The kind of friendly competition

that would emphasize the creation of items, or methods, to help the

home community, as well as others, live more effective and enjoyable

lives. A real “win-win” for everyone.

No comments:

Post a Comment